Kevin Webb, 32, cracks his bullwhip. It snaps like gunshot, and stirs up the morning dew so fine it resembles gun smoke. Little wonder: the braided leather whip travels 1,200 kilometres an hour.

Kevin Webb, 32, cracks his bullwhip. It snaps like gunshot, and stirs up the morning dew so fine it resembles gun smoke. Little wonder: the braided leather whip travels 1,200 kilometres an hour.

“I beat the livin’ daylights out o’ myself learnin’ how to crack the whip,” Webb says with a gosh-shucks smile and sweet-as-sarsaparilla drawl. He’s helping show folks around the Pawnee Bill Ranch and Museum, Oklahoma’s most visited historic site. It’s the former home of Pawnee Bill, who was second only to Buffalo Bill Cody as a star of Wild West shows in the early 20th century.

Webb learned the art of the bullwhip out of boredom, practicing on tin cans, newspapers and thin air. He says, “I held targets for my uncle when he practised the bullwhip, and eventually got better than him.” Every so often, he sets aside his job as the museum’s maintenance supervisor to show visitors some of the stunts that folks like Pawnee Bill made famous.

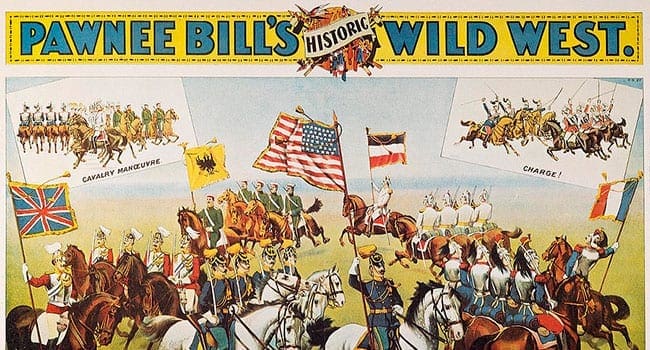

Such shows were popular from the early 1880s until just before the First World War. A theatrical exaggeration of life in the American West, they offered a heady mix of entertainment – shooting exhibitions, races, trick roping, and re-enactments of such historic events as Custer’s Last Stand.

“Those shows are directly responsible for the images in our heads of what the West was really like,” says Sarah Blackstone, dean of fine arts at the University of Victoria and author of two books on the subject. “They were the first real visual representations of the West that most people had ever seen.”

They even made rare events like stagecoach robberies and Indian attacks seem commonplace, she adds.

The most iconic Wild West showman was Buffalo Bill, a one-time buffalo hunter and army scout. But the flamboyant Pawnee Bill – born Gordon W. Lillie – was a close second. And at the museum, located on the property where Lillie lived for more than three decades, you’ll discover why.

Lillie was born in Illinois, but soon moved to southern Kansas with his family. As a boy he became enamoured with the West through dime store novels and a friendship he developed with the Pawnee Indians, who temporarily camped in Kansas during their forced exodus from Nebraska.

Lillie eventually became a teacher in the reservation school and joined the tribe’s annual buffalo hunt. Those experiences led him to join Buffalo Bill’s show as an interpreter for Pawnee cast members.

By the time he was 28, however, Lillie broke away to form his own troupe. Undaunted by a couple of financial reversals, Lillie toured both the U.S. and Europe, where he performed for royalty. He was so popular that dime-store novels were written about him.

At the show’s peak, cast and crew totalled 500.

Lillie even partnered with Buffalo Bill Cody when the latter encountered his own financial difficulties. The duo travelled for five years as the Two Bills Show. That operation was foreclosed in 1913 for debts Cody had racked up without his partner’s knowledge.

Lillie went on to ranching, but he also dabbled in banking, oil refining, filmmaking, publishing and tourism.

His fascination for the West also continued. He was instrumental in persuading the U.S. government to save the American bison from extinction by establishing a wildlife refuge and applying the brakes to sport hunting. And he created his own buffalo ranch, the basis of today’s Pawnee Bill museum just outside the Oklahoma town that bears his name.

The centerpiece of any visit is the 5,300-square-foot arts and crafts mansion that Lillie and his wife, May, a star sharpshooter in his show, built in 1910 at a cost of $100,000. It was up-to-date for its day. Features include Philippine mahogany walls and Parisian bathroom tile. It was one of the first homes west of the Mississippi to boast electricity and hot-and-cold running water.

“Everything in the house is original,” says Erin Brown, the museum’s collections specialist. “Well, everything except the fake food on the dining room plates.” That gold-glazed china was a set for 40 embossed with Lillie’s initials. The silverware was from Tiffany’s.

Other features also speak to the Lillies’ comfortable lifestyle. There’s a portrait of humourist Will Rogers, who was the first houseguest; a bust of Lillie sculpted by Gutzon Borglum, the man who carved the presidential heads at Mount Rushmore; bedroom furniture that was a gift from the Chinese government; and one of the world’s first electric toy trains.

And yet the house has a certain rustic quality, thanks to such touches as century-old Navajo rugs, leather furniture, and an umbrella rack made from an alligator that Pawnee Bill often wrestled in his show.

At the adjacent museum, exhibits detail the story of the Wild West shows and Pawnee life, with art and artifacts that range from an explanation of an earth lodge to the 1863 stagecoach used in the Two Bills show. Kids are able to dress in western clothing and try their hand with a lariat.

And with advance notice, visitors can jump on a tractor trailer to drive through the buffalo herd, many of which come from the state wildlife refuge Pawnee Bill was instrumental in creating.

IF YOU GO

Pawnee, Oklahoma, is located about 90 kilometers west of Tulsa on U.S. Route 64.

Between April and October, the museum is open Tuesdays through Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. and on Sundays and Mondays from 1 to 4 p.m. The rest of the year, it’s closed on Mondays and Tuesdays. Admission is $3, with reductions for seniors and youth. Information: www.okhistory.org/sites/pawneebill

Pawnee is also the birthplace of Chester Gould, creator of the long-running comic strip Dick Tracy. The tiny municipal museum houses a display of Tracy memorabilia, a main street computer store has the world’s largest Dick Tracy mural, and a parade on the first Saturday of October brings law enforcement officials to town to celebrate the birth of the cartoon in 1931.

BECOME A TRAVEL LIKE THIS CONTRIBUTOR

Contact us for details.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.